A not terribly brief history of spinning

- Gypsy Taylor

- Jan 28, 2016

- 5 min read

Spinning in various forms is very commonly an activity we see at reenactment events and medieval fairs all over the place. We know that spinning is the way we get threads and yarns to weave, naalbind and sew with. But where did it come from, who did the spinning and how did it change over time? Hopefully, I'll be answering a bunch of questions like this during this article, to help us understand the importance and evolution of spinning through history. (It's a long read, I'm not sorry :P )

In the beginning...

Many authors of papers and articles I've read agree that spinning in its most rudimentary form probably existed well over 10,000 years ago. Some suggest that a simple rock could have been used as an anchor for twines (twine simply being two or more strands of fibre twisted around each other) as they were twisted, or that the rock was in fact the first version of a drop spindle. I feel it's probably more likely that if any rock was involved it wasn't mankind's first discovery into twine production. It's probably far more likely that, after someone was playing with some kind of fibre and realised that twisting them together made them stronger, most primitive 'spinning' was most likely done by hand, resulting in twisted yarn. A figurine carbon dated to 25,000 BCE shows a woman wearing a loincloth, but there is still no clear verdict on whether the threads are twisted or truly spun.

After reading some articles that also suggested twisting by hand was likely, I tried it out. I tell you now, it's not something I'm keen to do on a regular basis! It is incredibly time consuming and my hands ached terribly after about an hour of it, not to mention it's not a fast method of twine production. However, it does allow the utmost level of control of the twine that can be produced, because it's so slow.

One major drawback of twisting by hand though, is that to get any decent length of twine, you either need a second person to help you, or you need something to wrap the twine around. This is the first evolution step. There is limited evidence to suggest that the rock was that next step. Some nomadic tribes in remote areas of Asia still spin using rocks, but there is negligible archaeological evidence to tell us how or where it was used historically.

Other authors suggest that simply wrapping the hand twisted twine around a stick was the next evolution, which seems logical, as it would allow the 'spinner' to create a longer thread without assistance, and would prevent the twine from untwisting before the twist could be set. And from twisting around a stick to spinning the stick itself, it's not an illogical step. The problem we have with evidence though, is that it is likely if there were any found in archaeological digs, they would likely be dismissed as an ordinary stick.

I have a cunning plan...

Somewhere along the way, some bright spark decided to put the rock and the stick together. The spindle and whorl are born. By adding a whorl (an interchangeable weight) to the spindle shaft, a spinner no longer needed to twist the fibres by hand, or roll a stick against their leg (although some methods of spinning did still do this, just with better efficiency). These whorls were made from materials like stone, metal, bone, wood and clay, with the heavier materials being the most common, but that didn't mean that the lighter materials weren't still valued and used often. In areas where the fibres accessible were generally shorter in length, a bead-whorl spindle was used, which is better for spinning finer yarns as there is not as much weight to break the yarn or thread as it is being spun. Some authors say that bead-whorl was probably the most common type of drop spinning throughout history, given the higher numbers of them being found in areas we know had significant fabric trade. These whorls were used with different shafts and in different combinations for different weight (or thickness) threads and yarns, all meant for different purposes. Some spindles would be spun with the tip touching the ground or supported by a specially made cup. As mentioned before, some were still used by running them across a thigh, and some weren't supported by anything except the yarn that they were spinning.

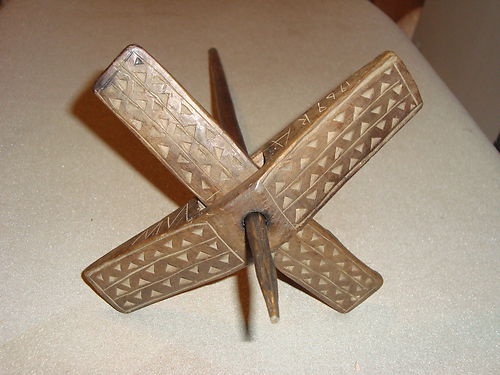

There are two types of spindle that didn't use a whorl as we know it; one was what we call today the "Turkish" drop spindle. It uses one or two cross arms that sit in the lower half of the shaft and as yarn is spun, it get wrapped around the arms instead of, or as well as, the shaft. The other is a spindle that is carved from a piece of wood and is shaped in a way that it essentially has the whorl built into it. (I have one like this, it's a lighter wood so it's very good for finer yarns, but if I wanted to make thicker yarns, I'd probably add a whorl)

All of these documentable types of spindles also seem to have been used in conjunction with a distaff, a stick that combed fibres were wrapped around to aid the spinner in feeding the fibres to the spindle.

The invention of the wheel...

Spinning wheels are first clearly depicted in art and historical records from 1234 CE (in Baghdad) but there is evidence to suggest that they were used in Asia from the 11th century CE. It should be said that these early wheels are not what we know wheels to look like today, as they had no rim. The wheel reached Europe in the late 13th century CE and by 1298, there were already regulations coming from what is now known as Germany regarding what kind of threads and yarns were not to be spun using a wheel. Warp threads for weaving were not allowed to be spun on wheels because spinning wheel produced a softer thread which couldn't stand up to the tension needed from warp threads.

These wheels would also have taken some time to master, I think. As they had no foot pedal (or treadle), the wheel had to be turned by hand and this would limit that hand's ability to help draught the fibres. To achieve evenness in the thread would take considerable practice.

The earliest evidence I have seen so far for a treadle spinning wheel comes from China, where a painter named Gu Kaizhi (born 344- died 406) painted an illustration for a book by Lie Nu Zhuan (also referred to as Liu Xiang) called 'Biographies of Exemplary Women.' There is also some talk of wheels in India from 750 CE. I still have more research to do on this one, as it seems to contradict a lot of other authors who say, as I mention above, that spinning wheels are seen much later. I'll update this when I know more. Flyer wheels are the last step in the evolution, really. It introduced a bobbin, which meant that the spinner did not need to stop and wind the thread or yarn onto anything themselves. A huge improvement if you ask me! The earliest we see these is somewhere around 1475-1480 CE, depending on who you ask. And pretty much anything after that, that was completely man (or more likely woman) powered, is just a variation on a theme. But the Industrial Revolution of 1750-1850 changed the game, and spinning wheels became a thing of hobbyists. With everything essentially automated, guilds shrunk and roles changed. That's all folks! Yup, I promise, until I find any more solid evidence or have more questions to answer here, I won't bore you with any more history on spinning. I hope this hase been helpful, and if you have any more questions you'd like answered, please find our group on Facebook, or email us and I'll answer you as soon as I can! Happy spinning!

Comments